Below is a downloadable article on “Understanding Shaft Voltage and Grounding Current of Turbine Generators” by Paul I. Nippes, PE and Elizabeth S. Galano.

Abstract

Attendant with the current practices of extending periods between turbine-generator planned outages is the need for improved and careful condition monitoring. By determining the condition of the turbine generator units and their suitability for continuing satisfactory operation, outages can be scheduled, often preventing forced outages.

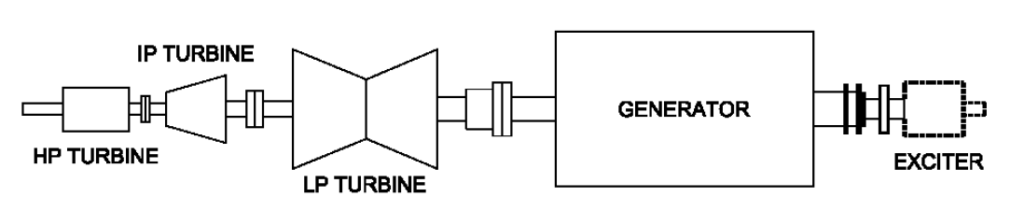

A relative newcomer to the field of monitoring is shaft condition monitoring, which also usually projects to train condition monitoring. This is accomplished by placing reliable shaft-riding brushes for shaft grounding and voltage monitoring. As can be imagined, a wide plethora of shaft grounding current and voltage data is available. The issue becomes one of sifting through to identify and project hidden messages as to the shaft, and unit condition. Illustrations and descriptions of shaft grounding currents and shaft voltages, based on measurements made on installed units is the main purpose of this paper.

Presented are results and practices employed over the past 25 years in monitoring turbine generator performance through interpretation of shaft grounding currents and voltages

Shaft Voltage Introduction

Stray voltages occur on rotating shafts in magnitudes ranging from micro-volts, to hundreds of volts. The former may be generated from shaft rotation in the earth’s magnetic field, or induced from electromagnetic communication signal induction. The latter can be induced by shaft rotation linking asymmetric magnetism of electrical machinery, by residual magnetism present in a shaft or in adjacent stationary members and by induction from switching of power electronics, exciters and/or current-carrying brushes.

Shaft voltages can be either “friend” or “foe”. As “friend”, they can warn, at an early stage, of problem development long before the problem is apparent on traditional monitors and instruments. As “foe”, they can, as a minimum, generate circulating currents, reducing unit efficiency and, as a maximum, the generated current can damage bearings, seals, gears and couplings, often forcing unit shutdown.

Control of shaft voltages can minimize the potential for damage. This control can be either passive, by simply placing grounding brushes, or active by injecting counteracting current signals onto the rotor. In both cases strategic brush placement and consideration is essential to satisfactory shaft grounding and signal sensing. Very important to the success of shaft grounding and signal sensing is the choice and reliability of plant grounding.